The Chán (Zen) Buddhist North Shaolín Monastery currently being reconstructed on Pan Mountain (盘山, Panshan) in Ji County (Jixian), 120 Km. north of Tianjin and 90 Km. east of Beijing in northeast China is in the imperial heartland of China and thus was exposed to much more direct mostly foreign aggression than the older headquarter Songshan Shaolín which is located closer to central China. Panshan (the location of the North Shaolín) has a strategic location in Jixian, and Jixian in China due to its location as a critical mountain pass from the sea inland, and from North to South not far inland from the eastern coast.

Jixian County (集贤县) is only 28 kilometers south of the Huangyaguan Great Wall (黄崖关 Huángyáguan– meaning Yellow Cliff Pass) located at the summit of high mountain ridges. With an unscalable precipice serving as a natural barrier in the east and sheer cliff serving as a natural wall in the west, the Huangyaguan Great Well possesses ferry and land passes, battlements, watch tower strongholds and large-scale barracks which collectively make this section of the Great Wall impregnable. It has always been a hotly contested spot in military history. According to historic records the Huangyaguan Great Wall was initially built in Tianbao 7th Year of the North Qi Dynasty (北齐, 550-557; 557). It was redesigned, tiled and overhauled by Qi Jiguan (戚继光, 1528–1588), the Commander in Chief of Ji Town during the Ming Dynasty.

The North Shaolín Monastery, originally called “Faxing Temple” was first built in the Wei Jin Dynasty (220-317). It is the oldest temple in the very large mostly rural Jixian area. According to the official Shaolín Temple internet site it became part of the Shaolín family under the auspices of Abbot Fuyu during the Mongolian rule of the Yuan Dynasty about a thousand years after Faxing Temple was first built, however that is a bit of an oversimplification.

In spite of its long noble history, ask most people in China where the “North Shaolín Monastery” is and surprisingly they say “Zai Songshan” (嵩山, at Song Mountain, Songshan) in central China. This suggests that the curious set of events leading to the destruction of the North Shaolín Temple – from the anti-martial policies of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and 1928 rumors of the arrival of a warlord bandit’s army, to May of 1942 during the 2nd Sino-Japanese War when it was burned to the ground – effectively erased even the memory of that glorious temple from the Chinese people.

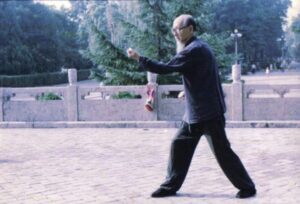

This isn’t to say or suggest that the North Shaolín monks went out in a blaze of glory fighting the Japanese at the Monastery, as that clearly didn’t happen, though indeed Japanese Imperial Forces did burn the Monastery down during a battle with resistance fighters, some of whom may have been monks or former monks, however the Monastery had been all but abandoned some years before for a variety of reasons. Instead, Northern Shaolín Kung Fu disseminated widely prior to the final destruction of the Monastery, especially in the Beijing/Tianjin/Pingu areas specifically and Hebei Province in general and thus a suicidal battle was avoided and maximum use of their unique skills was used rather than obliterated along with the monastery.

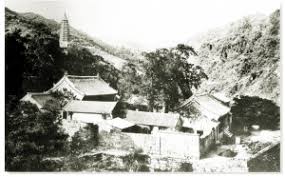

Following the destruction of the North Shaolín Monastery few remains existed of the original Monastery except for the foundations of a few buildings and one lovely white 13 tiered ancient pagoda from the early-mid Qing Dynasty which is currently in serious need of repair i.e. crumbling foundations under it, bullet holes in it and foliage growing on it. What wasn’t destroyed during the fighting was later looted. At present, the ancient Northern Shaolín Monastery is being rebuilt.

Brief Review of Songshan Shaolín Martial History

“In fact, Shaolín Quan was the manifestation of the wisdom of the monks of the temple, secular Wushu masters and army generals and soldiers. Shaolin Gong Fu originated from folk Kung Fu of the Central Plains. According to archeological records, the Kung Fu in the Central Plains developed at a certain level during the Eastern (i.e 206 – i.sz 25) and Western Han 25-220) Dynasties. The Qigong also accumulated rich experiences. The monks of the Shaolin Temple are mainly from the Central Plains, so some monks had already learned Gong Fu before entering the temple, and they taught each other after entering the temple. The Shaolin Temple always held the tradition of widely absorbing the best Gong FuPerformances from the monasteries and continued to improve upon them.”

Though Bodhidharma is revered as the first patriarch of Chán, there is no substantial evidence that he introduced martial arts to the Shaolín. The Chinese martial arts Shuai Jiao (a kind of wrestling similar to Judo in some ways) and Sun Bin Quan (孫臏拳, kicking/punching art that utilizes the full range of meta-strategies from the “Art of War”) were well evolved centuries before the establishment of the Shaolín Temple. The history of Chinese boxing dates as far back as the Chou Dynasty (112 – 255 BC) (Draeger & Smith 1969). Does this necessarily mean that Bodhidharma didn’t pass on a series of stretches and strengthening exercises to the monks at the Shaolín Monastery; one he may have learned in India or developed on his own to help keep the monks refreshed and wakeful during meditation? Religions have historically had always had secret traditions. For example, in Jewish tradition it was against the law to write down the oral laws given by God to Moses: “Torah she-be’al peh,” though after the fall of Jerusalem (1st Century AD) they were recorded in the Talmud (the “Learning”) and Midrashim (the “Interpretations”) and can now be found in most libraries.

Some secrets however are revealed more slowly. Hebrew theology was traditionally divided into three distinct parts. The first was the law (Torah) the second was the soul of the law (Mishnah) and the third was the soul of the soul of the law, the Kabbalah. The law was taught to all the children of Israel. The Mishnah was revealed to the Rabbis and teachers. But the Kabbalah was very cleverly concealed and only the highest initiates among the Jewish people were instructed in its secret mystic principles. “Kabbalah” means “secret or hidden tradition,” the “unwritten law.” However, these secret mysteries were written down and disseminated widely in the 18th and 19th centuries, though different versions have different levels of authenticity. No one however doubts the extreme antiquity of their origin or their Jewish roots.

Just so, it is possible that Bodhidharma passed on or created a series of stretching and strengthening exercises which were transmitted through the ages in secret at the Shaolín Monastery, and then in the 1800s some renegade monk perhaps revealed them to a wandering Taoist who “created” or more accurately revealed the so-called Yi Jin Jing. Certainly it could be a complete fraud; however no one can definitively conclude this. Thus, despite Yi Jin Jing’s questionable authenticity, it may have some foundation in ancient Shaolín tradition. Further research is required to definitively substantiate or refute the true origins of Shaolín Kung Fu, however it is a truism that some secrets of history are never fully revealed.

It is definitely true that neither Bodhidharma nor the Shaolin “invented” martial arts in China. Warfare is ancient in the extreme and martial arts play a key role in preparing for war. It is also definitely true that Buddhism was the central theme of the Shaolin Temples, and Chán Buddhism was founded in China by the Patriarch Bodhidharma.

Songshan Shaolin’s history of military endeavor outside the monastery is quite old too going back at least to the seventh century, specifically warding off bandits and subsequent support for the future Emperor Li Shimin’s (Emperor Taizong of Tang Dynasty) campaign against the former Sui Dynasty General Wang Shichong (620-621). In his book “The Shaolin Monastery History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts,” Dr. Shahar critically examines the dates of the origin of Shaolin Kung Fu, and notes that helping Prince Li Shimin’s defense of the realm against Wang Shichong was not proof or even very solid evidence that there was a “Shaolin Kung Fu” at that time, as the Shaolin warriors that fought against Wang Shichong might have been former soldiers. In an earlier article Dr. Shahar wrote that, “Furthermore, the literature of the ensuing Song and Yuan periods does not allude to Shaolin martial practice either.”

“Near the end of the Sui Dynasty things around the Shaolin Monastery were in a mess. There were thousands of thieves in the area. An old monk with a staff kept thieves outside of the temple. The old monks chose hundreds of young strong monks to teach them the use of the staff. The Shaolin Monastery got rid of the thieves.”

During the Five Dynasties Period (907 – 960) Shaolin Fuju invited 18 martial arts masters to help improve Shaolin martial arts. Fuju absorbed the best martial art techniques from others and compiled the Shaolin Quan. During the Jin and Yuan dynasties (1115-1234), Shaolin monk Jueyuan, Li Sou a famous martial artist from Lanzhou and Bai Yufeng, a famous martial artist from Louyang (entered the temple and took the name Qiu Yue Chan) created more than 70 Shaolin martial techniques. Shaolin Gong Fugradually developed from the Sui and Tang dynasties to the Jin and Yuan dynasties.

Though the Shaolin monks needed to protect themselves and their community, and were invited to work in service to the emperor many times in succeeding centuries, it was in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that military monks attained their greatest glory.

Even though the piracy war was their most famous, it was not the only campaign in which Shaolin monks took part. Beginning in the first decade of the sixteenth century, Shaolin warriors were regularly drafted to quell local unrest in North China. In 1511, seventy monks lost their lives fighting Liu the Sixth and Liu the Seventh, whose bandit armies swept through Hebei and Henan. In 1522-1523 Shaolin fighters battled the miner turned bandit Wang Tang, who pillaged Shandong and Henan, and in 1552 they participated in the government offensive against the Henan outlaw Shi Shangzhao. “The monastery’s military support of the Ming continued into the dynasty’s turbulent last years. During the 1630s, Shaolin monks were repeatedly enlisted to the doomed campaigns against the swelling rebel armies that by 1644 were to topple the dynasty.”

“During the Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty (1522 – 1566), the Shaolin Temple sent more than 80 martial monks to fight the Japanese pirates and defeated the enemies. In the 40th year of the Jiajing reign (1561) Ming General Yu Dayou (1504 – 1580), who was reputed for his anti-Japanese military service, went to teach cudgel-fighting skills in the Shaolin Temple. After this, Shaolin monks switched from cudgel fighting to fist fighting, so fist fights could be promoted to match cudgel fights. At the end of the Ming, Shaolin monk Hong Ji also learned outstanding spear fighting skills from Liu Dechang.”

As reward for the Shaolin Temples’ support of the Ming dynasty they were protected from numerous purges by succeeding anti-Buddhist Emperors of which there many – who mostly favored the domestically brewed religions Confucianism and to a (much) lesser extent Taoism. By late Ming dynasty the role of military “monk” had grown to truly epic proportions leading to criticism inspired by envy, corruption or fear and possibly all three. This prejudice continued into the Qing Dynasty, no doubt for similar reasons.

“In 1832, for example, a Dengfeng Country magistrate issued a strict warning to the Shaolin Monastery concerning the behavior of its subsidiary shrine monks, whom he accused of not only dietary transgression, but also of sexual offences. Shaolin-affiliated monks, magistrate He Wei (fl.1830) charged, engage in drinking, gambling and whoring.” – Shahar (2008)

The monks were also accused of “colluding secretly and collaborating in all sorts of evil.” Interestingly, the October 14th 1307 arrest of the Templar knights in France was accompanied by a long list of charges including “secrecy,” which was only a precursor to the November 22nd 1307 Papal Edit ordering the arrest of all Templar knights across Europe and seizure of their properties and assets. This rather negative view of some Shaolin “monks” (Wusengand/orSengbing) however was not the popular vision of the romanticized “warrior monks” and the trend of increasing power of the Shaolin increased through most of the Qing Dynasty in spite of the dynastic leader’s escalating fears regarding that very same power.

Origin of the North Shaolin Monastery

The North Shaolin Monastery was founded and formally named following the resolution of a 30 year conflict between Taoists and Buddhists on Panshan. According to the official Shaolin Temple site: “In 1245 Fuyu (1203-1275) was appointed by the first Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty Kublai Khan as the abbot of (Songshan) Shaolin Monastery before the former took the throne.” (Shaolin.org, “Fuyu”) Fuyu’s good friend Yelu Chu Cai, also a Buddhist was reputed to be Genghis Khan’s foremost warrior at that time. Fuyu had earned extraordinary merit in a variety of ways, for example he was famous for inviting martial artists from all over China to the Songshan Shaolin Monastery to harmonize the best of their techniques into an even wider and more effective Shaolin curriculum. Fuyu was given permission by the Khan to open five other temples, one of which was 70 years later to become the North Shaolin Monastery (Panshan Zhi).

Thirty Year Buddhist/Taoist Conflict and Historical Records

In 1286 Taoists who reportedly had “great power” led by Zhang ZhiGe gradually started moving into many temples in the Panshan area including Faxing Buddhist Temple, (later to become ‘North Shaolin Monastery’). After staying for a while they reported to their Quanzhen (全真) Taoist masters how nice it was and then they completely took over, (allegedly) smashed some Buddha statues, burned the main hall, and destroyed the white pagoda tower, which they later denied and instead blamed on the Buddhists. The Panshan Mayor at that time however liked them and disregarded the accusations. (Buddhist Website, 2009, Gao, W. 2009, Panshan Zhi – Qianlong version)

The Quanzhen Taoists were popular because of their good relationship with Genghis Khan, initiated when the Khan heard about the teachings of Qiu Chuji (丘处机, 1148–1227) and invited him to a discussion which occurred between April 14th and May 12th 1222 in the Hindu Kush Mountains in what is now Afghanistan. Qiu urged the emperor to be less brutal in his conquests and instructed him on the basic principles of cultivating health and longevity. In the words of author Stephen Eskildsen in his 2004 book “The Teachings and Practices of the Early Quanzhen Taoist Masters,” “As a result of this mission, Qiu is said to have saved many lives.” Genghis Khan also decreed that all Taoist monks and nuns in his domain were to operate under the authority of Qiu Chuji. (P. 17) As word of these actions rippled out, the locals on Panshan and elsewhere within the Mongol domain were favorably inclined toward the Quanzhen Taoists. Then the Taoists applied to the Jixian government for ownership of the temples, which in turn applied to the Emperors mother. The Empress Dowager changed the name of what was then Faxing Temple to “Cloud Taoist Temple.”

In 1315 an honored Buddhist monk – Fuyu’s student and successor Yun Wei (his Buddhist name, also sometimes called “Chao Yun”) looked at the damaged temple and went to appeal to the Mongolian Court.

Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan, (reign: April 7, 1311 – March 1, 1320; also known as Emperor Renzong of Yuan 元仁宗) residing in “Datu” (capital of Yuan Dynasty at that time and current location of Beijing) hosted a grand debate between the Buddhists and Taoists and ultimately decided in favor of Yun Wei the disciple of Fuyu and officially changed the name to “Bei Shaolinsi” North Shaolin Monastery (Buddhist Website, Panshan Zhi – Qianlong version). Then Yun Wei came back to Faxing Temple/Cloud Taoist Temple and broke the Taoist’s “stone,” (like a signboard declaring the temple’s name: “Xi Yun Guan” meaning “Stay on the Cloud”).

There are some discrepancies in the historical records of this time, i.e. different versions of the Panshan Zhi (Pan Mountain History, e.g. Qianlong and Zhi Pu) and they are somewhat at odds with the oral traditions that still exist on Panshan. What everyone does agree on is that Taoists took over Faxing Temple in 1254, and Buddhists got it back around 1315 under the auspices of Fuyu’s successor Yun Wei at which time it was named: North Shaolin Temple. According to oral tradition on Panshan Mountain however the temple was (also) called: “You Ji Shao Lin Chan Yuan” (“You Ji” is a very old name for Jixian County and “Chán Yuan” means Chán – Zen Temple; Source: 集賢少林禅官, interview with Yang Li Min, accountant for Wa Yao Village wherein the North Shaolin Temple is located). It seems virtually everyone in Wa Yao Village has knowledge of the Monastery and its history. Incidentally, “Wa Yao” means “roof-tile kiln,” referring to the fact that the ancestors of the people in that village moved there specifically for work making construction materials for the many temples on that mountain, principally roof tiles and bricks, though these days it is a widely scattered collection of farms and guest houses located on the paradisiacal Panshan mountain.

The most widely read Panshan Zhi (盤山志), or history of Panshan was part of a massive collection of writings and artwork collected and sponsored by Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799). “It is not surprising that one of Qianlong’s grandest projects was to assemble a team of China’s finest scholars for the purpose of assembling, editing, and printing the largest collection ever made of Chinese philosophy, history, and literature. Known as The Four Treasuries project, this mammoth undertaking spanned the years 1773 to 1784 and required the careful exam¬ining of private libraries to assemble a list of around eleven thousand works from the past, of which about a third were chosen for publication. The works not included were either summarized or—in a good many cases—scheduled for destruction on the grounds that they contained scurrilous material, revealed important geographical information that might be of use to China’s enemies, or else insulted the Manchus in some way. The Four Treasuries was thus a true symbol for Qianlong’s reign: carefully planned, historically ground¬ed, culturally sophisticated, but at the same time massive, intrusive, and coercive. The Four Treasuries project, or Siku Quanshu (四庫全書), published in 36,000 volumes, containing about 3450 complete works and employing as many as 15,000 copyists was also an excellent way to permanently silence political opponents.

Thus, it should not be terribly surprising that Panshan oral traditions are often quite different from the official versions of the history, and furthermore constitute an extremely interesting and colorful mix of legends and history. One of their stories about Emperor Qianlong goes as follows: As a boy Hong-Li (the emperor’s given name) was often sick and people around him said it was his destiny to become a monk as at that time it seemed unlikely that he would become the emperor. He then made a promise that if he could become healthy he would become a monk. But later he became healthy and the emperor so he found another man, Zhi Pu from Panshan who was born on the same day, month and year as him to take his place as a monk. It was Zhi Pu who wrote the Panshan Zhi (盤山志) and one reason Emperor Qianlong so loved Panshan. (Interview with Xu Wen – Wa Yao Village Mayor). Colorful as this story is, it is also rather unlikely. Zhi Pu (智朴) was born in 1636 and a friend of Emperor Kangxi, Emperor Qianlong’s grandfather. (Baidu Encyclopedia: Zhi Pu) Interestingly, Emperor Kangxi’s father, Emperor Qianlong’s great-grandfather Emperor Shunzhi was very much a contemporary of Zhi Pu being born in 1638. Accidentally substituting Emperor Qianlong’s name for Emperor Shunzhi would be an easy mistake for a story teller in Panshan to make sometime during the past nearly 400 years given that Emperor Qianlong did visit Panshan some 32 times and he had dozens of his poems extolling the beauty of Panshan carved into the huge stones on Panshan many of which still can still be found today.

Emperor Qianlong was born in 1711 and though he may have met Zhi Pu, the emperor would have been very young and Zhi Pu quite old. Emperor Qianlong did however like Zhi Pu’s Panshan Zhi (盤山志) and it was clearly admired by his grandfather Emperor Kangxi. One difference between the original Zhi Pu Panshan History and Emperor Qianlong’s Panshan History is that the Emperor’s redacted version is full of praise for the Emperor, whereas Zhi Pu’s was focused solely on Panshan.

Regardless as to differences between historical texts and oral traditions, Buddhists and Taoists in China have in some ways integrated in China. Nowadays large Buddhist temples often have a Taoist hall somewhere and Taoist temples often have some token alter for Guan Yin or other Buddhist semi-god/goddess. In the Songshan Shaolin Temple one can find a large black stone engraved with a picture of a rather round vaguely monk-like character with symbols integrated on his personage depicting the three major philosophies in China dedicated to the “Three Teachings” called: San Jiao He Yi (三教) imparting a message of harmony between Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. This integration however did not apparently happen on Panshan per se, as there are or were 72 Buddhist temples on the mountain and not one Taoist temple. Locals have fearsome stories of Taoists leading cults that result in people being possessed by animal spirits and other odd things, though their martial prowess is often extolled as well.

It is worth noting however that Baita (Buddhist) Temple in Panshan town (about 200 meters from Dulesi Temple) has a Palace of the Goddess with a sign that says: “This palace was built in the Ming Dynasty and rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty. It is a well-known Taoism area in Jixian district and its surround areas. The new site of the palace was built in 1993 and the images of Taoist figures were remodeled.”

Jixian History and the Monastic Order

The cooperation between Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan, Fuyu and Yun Wei was after at minimum of 700 plus years of North Chinese martial valor repelling Mongolian invaders that finally succeeded in conquering China, and Jixian was in the thick of it throughout. The Huangyaguan Great Wall (557 AD) referred to above protected Jixian from direct northern attacks, however didn’t stop invaders from basically going around it further to the east and west.The major construction of the “modern” Great Wallof China began in the Ming Dynasty (1388-1644 AD). For some 1,500 years at least Jixian has been a crucible of Chinese military forces in civil wars and wars against foreign invaders. During the transition from Ming to Qing Dynasty (c. 1644) there were three massacres of large portions of the Jixian population by Qing Dynasty military forces attributed to policies of Emperor Hong Taiji (1592 – 1643) considered to be the first true emperor of the Qing Dynasty by “virtue” of his vast conquests, though he died shortly before his conquest of Beijing, a job finally finished by this son. The fact that the Jixian militia survived three massacres suggests that the people there 1) exhibited extraordinary martial valor, and 2) were exceedingly resilient to genocide. This isn’t to say that the NorthShaolin Temple as an institution was involved in a large number of military engagements per se, but rather it survived in an exceedingly deadly neighborhood andWuseng warrior monks (as compared to Biqiu, fully ordained monks) were recruited into the temple area as the need arose.

During the late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Songshan Shaolinmonks along with NorthShaolin monks and others e.g. from Mount Wutai (五台山 Shangxi) and Mount Funiu (伏牛山 Henan) repeatedly distinguished themselves fighting against Japanese pirates supported by other foreigners and Chinese bandits called “Wokou” (倭寇 Wokou) who relentlessly raided coastal towns on the eastern coast of China. The Ming Dynasty General Tang Shunzhi (唐顺之) from North Shaolin fought Japanese Wokou in Jiangnan until his death (martyrdom) there.

But it was another Shaolin trained Chinese General, martial artist, poet and weapons inventor that finally defeated the pirates, Yu Dayou from a junior officer’s family in Anhui. (1503–1579). According to Dr. Meir Shahar, author of The Shaolin Monastery History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts:

“Their (the pirates) attacks were especially severe along the Jiangnan coast, where they pillaged not only the countryside but even walled cities. In 1554 for example, the city of Songjiang was captured and its magistrate put to death. The government encountered tremendous difficulties in its attempts to control the situation, partly because the local authorities were themselves involved in trade with the bandits and partly because of the decline of the regular military. It was not before the 1560s when order was restored to Jiangnan, partially through the efforts of the above-mentioned generals Yu Dayou and Qi Jiguang.

Several sixteenth century sources attest that in 1553, during the height of the pirates’ raids, military officials in Jiangnan resolved to mobilize Shaolin and other monastic troops. The most detailed account is Zheng Ruoceng’s (1505-1580) “The Monastic Armies’ First Victory” (Sheng bing shou jie ji”), included in his The Strategic Defense of the Jiangnan Region (Jiangnan Jing Lue) (preface 1568)…”

“The monks scored their biggest victory in the Wengjiagang battle. On July 21, 1553, 120 fighting monks defeated a group of pirates, chasing the survivors for ten days along the twenty-mile route southward to Wangjia-zhuang (on the Jiaxing Prefecture coast). There, on July 31, the very last bandit was disposed of. All in all, more than a hundred pirates perished, whereas the monks suffered four casualties only. Indeed, the monks took pity on no one in this battle, one employing his iron staff to kill an escaping pirate’s wife.

“Not all the monks who participated in the Wengjiagang victory came from the Shaolin Monastery, and whereas some had previous military experience, others presumably were trained ad hoc for this bottle. However, the cleric who led them to victory did receive his military education at Shaolin. This is Tianyuan, whom Zheng extols both for his martial arts skills and for his strategic genius. He elaborates, for instance upon the ease with which the Shaolin friar defeated eighteen Hangzhou monks, who challenged his command of the Monastic troops…”

That North Shaolin monks would not have participated in this military action is inconceivable. Jixian, formerly called Jizhou, (and before that Yuyang 渔阳) home of the North Shaolin has its own story of martial valor dating back at least as far as the Northern Qi Dynasty’s (550 to 577) construction and defense of the great wall long before Faxing Temple joined the Shaolin family in 1315. Thus Jixian had its own form of war hardened “Folk Wushu,” predating and later influencing and being influenced by North Shaolin Kung Fu, and consequently also Songshan Shaolin Gong Fustyles as well.

The Royal Road on Panshan

One factor that led to the North Shaolin Monastery being built so beautifully within the paradisiacal Pan Mountain range was that it enjoyed the favor of many emperors for over 1,500 years.

There once was a royal road leading up to the North Shaolin Temple from below along which many Emperors of China from the Three Kingdoms period to the end of the Qing dynasty walked. This royal line stretched from Wei Emperor Cao Cao (曹操 155 – 220), Emperor Liao Taizong (辽太宗, 902 – 947) and so on until the Qing Dynasty Emperor Kangxi (康熙, 1654-1722), his grandson Emperor Qianlong (乾隆帝, 1711-1799), Emperor Jiaqing (嘉慶帝, 1760 – 1820), and Emperor Daoguang (道光帝, 1782 – 1850). Many are the stories about these royal visits. It is said that Emperor Liao Taizong wrote several poems about Panshan of which the following is a part:

“The Jade green fields

A journey filled with adornments

The mountains geological beauty

Like a talisman

Always increasing, enduring like an ocean

The air – a hundred kinds

The pine trees so tall a canopy

There is no need to rush or change

outside the city.”

A thousand years later Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong first inspecting Panshan excitedly said: “If I had known the beauty of Panshan, why would I have lived in the south?” (Buddhist Website, 2009)

Emperor Kangxi visited North Shaolin Temple many times as did Emperor Qianlong who had part of the North Shaolin Temple rebuilt, some of his officials live at the Temple, made laws protecting the forests in the area (especially the chestnut trees) and even built a palace nearby for himself and family. So beautiful was Panshan that his mother came often and spent considerable time at their new palace, North Shaolin and other nearby temples.

Unfortunately, the Royal Road was cut when a large dam was built in 1993 about a kilometer below the Temple and is mostly forgotten now except by locals, though many parts of that ancient stone pathway from the original road remain in the area. It leads up right beside the North Shaolin Monastery and up further through the Ta Lin (塔林, pagoda forest graveyard) of “Zhong Fa Si” (中法寺), meaning Middle Law Temple (because it’s midway up the mountain) to other temples and (locally) famous caves and locations in the mountains. Zhong Fa Si was the ‘central’ monastery on Panshan; it was the training center for most of the monks that went to the 70 temples on the mountain. It was a very large temple.” It is locally believed some or many of the monks at Zheng Fa Si had been Wang Ye or cousins of the Emperors. The father of Emperor Kangxi, the Shunzhi Emperor (順治帝, reigned 1643 – 1661) and first Qing Dynasty Emperor to rule over China gave up the throne to his son Kangxi to become a monk. Thus, it might not be a great surprise that some or even many royal cousins and other family members might follow this tradition and enter the monastery. (November 17th, 2013 interview with Mr. Yao, the Taiwanese American gentleman who rebuilt Zong Fa Si’s Ta Lin starting in about 2005.)

Though that temple was also destroyed during the burning of the mountain in 1942 by the Imperial Japanese army, the remains are more intact, partial buildings at least, than North Shaolin which was virtually obliterated except in the hearts and minds of the Shaolin survivors and some local people. Temples can be distinguished from palaces on Panshan by the color of the stones that remain. The emperors virtually always imported their stones which tended to be more pink colored than the local gray, brown granite stones.

Red Dragon Pond

Though most of the North Shaolin Temple was destroyed during conflicts from 1928-1942, there were actually two survivors, the beautiful 13 story Baofou White Tower/Pagoda on a hill in the mountain adjacent to the old temple grounds, and at the foot of that hill is “Red Dragon Pond.” Locals say that it never dries up and is an amazing beauty. There is a dragon engraved into the stone. On a sunny day the dragon can be seen rippling on the water as if it was swimming through the water. There are many legends about the Red Dragon Pond like the following: The East China Sea Dragon King’s grandson Red Dragon, after seeing Panshan region’s utter desolation from drought sent a heavy rain despite a ban on such things by the Dragon King. He then ran to the Crystal Palace and asked the Dragon King: “Why do we have a thousand areas of boundless expanses of water, but thirsty are the people?” Dragon King, none too pleased locked up Red Dragon. Later, Red Dragon secretly ran out and fixed up the pond with an abundance of water that never runs dry. Since then, Panshan has had abundant harvests.

Decline and fall of the North Shaolin Temple

The roots of the destruction of the North Shaolin can be traced to early Qing Dynasty wide-spread repression of martial art training, probably having something to do with the Shaolin supporting the Ming Dynasty till the bitter end and rumors that the Shaolin may have supported other anti-Qing government rebellions, like the White Lotus Rebellion (川楚白蓮教起義, an anti-tax movement 1794–1804) and Boxer Rebellion (義和團運動, anti-foreign imperialism movement 1897-1901), though the North Shaolin had some but not complete immunity from that anti-martial education movement by virtue of its relationship with 4th Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong (1711 – 1799) his special love for the temple as well as many other preceding and succeeding emperors who shared his sentiments. The suppression of martial arts training did have some negative impact on the North Shaolin Temple specifically in the form of a somewhat lower population of monks (Gao, W. 2009).

Warlord Era and the Buddha’s Belly In 1928 rumors started spreading that Dulesi Temple (独乐寺), about 10 kilometers down the mountain from the North Shaolin Temple had a large Buddha with pearls in its crown and treasures in its belly. Hearing these rumors, the leaders of Dulesi Temple asked the monks from North Shaolin to assist given that a particularly voracious warlord named Sun Dianying (孙殿英 1887–1947, who at first fought against the Japanese until his defeat, then fought for them against Chinese) was on his way to (violently) collect those treasures. This was after all the “Era of the Warlords” in Eastern China (1916-1928) when the country was despotically ruled by a collection of large murderous well-armed gangs of bandits some of which had up to half a million men. The Era of the Warlords came about as the result of several factors, including the Qing Dynasty’s loss to the European powers (specifically and primarily Britain in the Opium wars), and secondly a relatively high level of corruption throughout the empire which included widespread slavery and crushing poverty. The fall of the Qing Dynasty left a power vacuum which the Warlords filled ruthlessly. The destruction of both Songshan and North Shaolin Monasteries was the direct result of the many failures of the Qing Dynasty leadership.

“The Qing court and foreign aggressors had collaborated from 1860 on to suppress the Taiping Revolution (太平天国运动). The American adventurer Frederick T. Ward, conspiring with the Qing officials and their agents in Shanghai recruited foreign mercenaries and organized them into a Foreign Rifle Detachment. Britain and France also sent troops to join the Qing campaign, while Russia supplied the Qing government with 10,000 rifles and fifty cannon along with troops to intercept the Taiping’s attack… The domestic and foreign counter-revolutionary forces there gained a reprieve as the Taiping army had to back off and return to defend Tianjin which the Qing troops had again besieged.” On 12 February 1912, Empress Dowager Longyu (孝定景皇后, Xiao Ding Jing 1868–1913) issued an imperial edict bringing about the abdication of the child emperor Puyi (溥儀, 1906–1967). This brought an end to over 2,000 years of imperial China and a few years later resulted in a 12 year period of warlord factionalism. The number of rebellions and loss of life following the Opium war in China is staggering to the imagination:

Effects on the Shaolin Monasteries

Ninety percent of the Songshan Shaolin was burned in 1928 by the Warlord, Shi Yousan (石友三, 1891–1940). A question arises as to about how many warrior monks the whole Shaolin extended family had. According to Shaolin Abbot Shi Yong Xin (释永信):

“Since the famous Shaolin abbot Xueting Fuyu (雪庭福裕, 1203–1275) established Shaolin’s hereditary succession and branch system, Shaolin Temple had since become the nucleus of a cluster of branch monasteries that are situated around Shaolin Temple. Shaolin Temple had a total of forty branch monasteries during its most prosperous period, with most of those monasteries situated in the Central Plains region. “Most of these branch monasteries are of the Caodong lineage and their monks are part of Shaolin’s hereditary succession system. In fact, those who were in charge of Shaolin’s affairs were all chosen from these branch monasteries, resulting in a continuous thriving pool of talented monks. It was exactly the hereditary succession and branch systems that allowed long period of stability and cohesiveness that contributed to Shaolin Temple’s continuous prosperity.”

Having some 40 branch temples suggests that the Songshan Shaolin may have had many hundreds or even thousands of monks as part of its extended family. “In 1922, Miao Xing, who had served as a regimental commander in the army, became the acting abbot of Songshan Shaolin. He accepted a large number of monks and layman disciples, and led them to eradicate bandit gangs in the local vicinity. Three years later Heng Lin, then acting abbot, gathered a large number of monk warriors for an oath-taking ritual at the temple. But this expansion of the order was not enough. In 1928, Shaolin Temple took its most serious blow. A warlord name Shi Yousan set fire to the temple. It burned for over 40 days, destroying 90% of the buildings. Many of Shaolin’s most precious relics were looted. Its massive library of Buddhism and Gong Fu was reduced to ash. Shaolin would not recover from this destruction until the late 1980s.”

Regardless as to the exact number of monks at Songshan Shaolin, or under the Shaolin umbrella, the North Shaolin Temple was always significantly smaller than the Songshan Shaolin Temple. After the rumors regarding the arrival of a Warlords army’s imminent arrival (1928), some monks from both Dulesi and North Shaolin started leaving the temples. Siege warfare is not profitable for those within wooden temples. By virtue of the monks leaving the North Shaolin Monastery, the Temple was spared destruction during the Warlord Era in China and the monks survived to apply their special skills elsewhere primarily in Hebei province. According to North Shaolin historian Gao Wenshan (2009) the monks didn’t completely abandon the North Shaolin in 1928 but the number of monks declined significantly, though “weapons racks remained near the front gates and the remaining monks continued to teach.”

Japanese Invasions

In 1931 Japan invaded China first taking over Manchuria in the Northeast as a follow-up on the assassination of the local warlord Zhang Zuolin (张作霖, 1875–1928), June 2nd, 1928.

In 1937 Japanese expanded their domain in North East China taking Beijing and Tianjin in a matter of weeks following their July 7th attack. Cities were relatively easy for foreign invaders to pound with artillery into submission, but mountain folk especially in Jixian proved vastly more challenging. Mountain people are tough, especially Jixian people with their nearly two thousand year legacy of martial valor. That Buddhists in general and the remaining Shaolinmonks in particular had some sort of intelligence gathering and sharing mechanism in place seems likely, and being better educated (e.g. literate), having maps, etc., certainly would have made them desirable candidates for leadership roles within the resistance movement for Northeast China, mainly based in nearby Tianjin. Shaolin monks were not the only Buddhist candidates to defend the nation.

“During the Anti-Japanese War, Ven. Master Taixu sent an open cable to the whole nation immediately after the July 7th Incident in 1937, calling on Buddhists across the nation to “heroically defend the country”, organizing them into rescue units in direct participation in the Anti-Japanese War. He also went abroad to reveal the appalling inhumane atrocities committed by the Japanese aggressors. Ven. Master Yuanyin remained faithful and unyielding and manifested a lofty national integrity in spite of the horrible torture he suffered in the Japanese prison. And Ven. Master Hongyi put forward an advocate, “Remembering to rescue the nation while chanting Buddha’s name, and chanting Buddha’s name when going to the rescue of the nation,” All this demonstrated to the full the great patriotism cherished by China’s religious communities. The bravery and courage displayed by the monks moved and inspired the whole nation so profoundly that appeals were made by the press across the country to “learn from monks.” Looking back on our history, we come to realize that such spirit is still our matchlessly valuable resource for conducting education in patriotism.”

Ven. Xuecheng (学诚, 1966-), Abbot of Guanghua Monastery (广化寺), Fujian Province, 2002

Mountain people, like those in Jixian, have the advantages of mobility and concealment. They are not so vulnerable to artillery or air attacks as people in cities like Beijing and Tianjin due to that mobility and tree cover. They’re also experienced hunters and trappers. Jixian like any wide area is composed of a number of clans which sometimes cooperate and sometimes compete; however when faced with a foreign aggressor, they put local differences aside and cooperate in many ways.

Shaolin Diaspora Theory

In 1928, Shi Yousan (1891—1940) a powerful warlord burned some 90% of the Songshan Shaolin. On June 2nd, 1928 the Japanese assassinated another powerful warlord in Northeast China (called “Manchuria” by foreigners) and installed the deposed Qing Emperor Puyi as puppet emperor heralding in an era of exceptional cruelty in that vast land area.

Given that Buddhism and tea culture traveled along the same routes in both China and Japan, it is entirely possible Shaolin intelligence regarding Japanese intentions was rather good. A plan for the Shaolin monks to disperse around (primarily Eastern) China in order to prepare the nation for the upcoming war would seem logical(though empirical historical evidence for this is lacking at this time). However, why else would most of the monks have left North Shaolin Monastery as early as 1928? On one hand, they might have been ordered to leave to protect the temple itself. Also, they might have been ordered to come to Songshan Shaolin to help rebuild. However, it is also possible there was a diaspora of Shaolin Monks around Eastern China to prepare the Chinese people for the incipient Japanese invasion.

Coincidence or not, the Guanghua Monastery (about two kilometers south of Putian city at the foot of Mount Phoenix and home of Abbot Ven. Xuecheng, quoted above) is located in Fujian Province, also home of the somewhat controversial “South Shaolin Monastery.”

“Approximately 500 warrior monks, led by a legendary Shaolin cudgel fighting monk Dao Guang, were sent to Fujian to fight against the pirates in the early 7th Century. “The monk warriors used their special talents, helping local Tang soldiers to suppress the invasion successfully, but quite a number of them died in the battle. Preparing to return to Songshan Shaolin Temple local people asked them for ongoing protection. For the burial of the dead monks and to grant the people’s wish, Dao Guang and his warrior monks got the Abbot’s permission from Songshan Shaolin Temple and settled down in Linquan Complex in Putian.”

The Japanese were exceptionally angry and vengeful in regards to Shaolin Monastery during the closing years of the war. This level of cruelty towards Buddhist monks was unusual even for the Japanese given the fact that Japan is primarily a Buddhist country, and Japanese Buddhism came primarily from China. Also, the Japanese by in large left monasteries alone provided they weren’t working with Chinese resistance movements. Whether or not there was a South Shaolin is not really important here, however Fujian has several port cities, was (and is) a major trading center for silk and tea, and would certainly have had connections with Buddhists all over China providing valuable commodities as it did, and thus was a likely location for the collection and dissemination of the most valuable commodities of them all, information. Training in paramilitary resistance fighting would seem a logical extension of their efforts given their history and current war with Japan. Fujian Province is one of the provinces of China with the greatest number of Buddhist temples (it is quite mountainous and Buddhist monasteries and temples are usually build on mountains) and also one of the most highly productive tea growing areas of China (the co-evolutionary relationship between the spread of tea culture and Chan Buddhism in China is documented in Chapter 4 – The Original Chinese Chán Buddhist “Way of Tea”). Though none of this is proof of a Shaolin Diaspora in 1928, various histories do confirm most of the Songshan Shaolin was burned in that year, the North Shaolin Monastery mostly (but not entirely) abandoned and the Japanese were making major advances in North China as a prelude to further invasions to the south. Thus a diaspora to train Chinese resistance fighters is not inconceivable.

Jidong Rebellion

It was only natural that the Chinese fought back (in an organized manner) against the Japanese offensive, beginning in 1937 with the “Jidong Rebellion” (East Hebei Rebellion) called: “Jidong da Baodong” (冀东大暴) in Chinese. Panshan was the Jidong Rebellion base (Baidu Encyclopedia: Jidong Rebellion) which followed in the wake of the Japanese military moving south from Beijing through and including Jixian County. They recorded successive wins against the Japanese till the end of 1938. This rebellion was attributed to orders passed down by the CPC Central Committee and the Northern Bureau. The Japanese however, counterattacked and retook much of what they lost. As if that wasn’t bad enough, in 1939 a large group of well-organized bandits broke into the North Shaolin Temple, tied the few monks that remained and temple workers in the stone mill outside the Shaolin temple, smashed many pagodas and the temple was looted. (Gao, W. 2009) In the early 1940s there were only two disciples caring for the Shaolin Temple who were then killed in the temple, leaving it unattended. (Ibid) What is surprising is not that the North Shaolin was destroyed, but rather that it survived so long, given that assertive righteousness doesn’t last long in an environment ruled by absolute tyranny and supported by the most advanced weapons in the world – gleaned from the European powers since the beginning of the Meiji Restoration – which the Japanse had.

Great Campaign of One Hundred Regiments

The Jidong Rebellion was followed by the CPC coordinated “Great Campaign of One Hundred Regiments” (August 20, 1940 – December 5, 1940) (百团大战 bai tuan da zhan: 八路军与日军在华北地区的一次规模最大战役) which also occurred in Hebei, the province wherein Panshan could be found at that time (hebei.gov, 2009). (Jurisdiction of Panshan changed in 1972 from Hebei to Tianjin.)

Sanguang politics

The Japanese responded to this “Great Campaign of One Hundred Regiments” with the Sanguangpolitics (三光政策 Sanguang Zhengce)the infamous “three cleans,” robbing, burning, and killing until “clean.”Though initiated in 1940, it only came into full effect in 1942. The Japanese called it the Three Alls policy(光作戦 Sanko Sakusen).

Also, gas and biological weapons were also used delivered from Japan’s Unit 731. The “research” done by this infamous very large scale chemical and biological weapons center included live vivisection on prisoners of war without anesthesia after infecting them with diseases, and all kinds of “surgical procedures,” as well as weapons testing on live prisoners and germ warfare attacks which included spreading plague fleas, infected clothing and infected supplies encased in bombs dropped on various targets. The resulting cholera, anthrax and plagues were estimated to have killed at least 400,000 Chinese civilians.

The fact that Jixian was subjected to repeated extreme counter offences during the war of resistance against Japan is reminiscent of their role fighting against the incoming Qing Dynasty when they were reportedly massacred three times during the 1600s. In May of 1942 in an anti-Japanese armed siege the North Shaolin Temple was burned. (Gao, W. 2009) This is not surprising given that Chinese resistance soldiers held meetings at the North Shaolin Monastery during the 2nd Sino-Japanese war 1937-1945. The North Shaolin Temple was then looted of what little remained, primarily building materials like roof tiles and bricks. (Gao, W. 2009)

Finding the location of the true North Shaolin after the wars

Because the Songshan Shaolin library was burned in 1928 and the North Shaolin so obliterated in 1942,after the wars no scholars knew the exact location of the former North Shaolin Monastery. Even finding where it had been was quite difficult after the wars when peace returned and people finally had a time and resources to try to recover some of the huge past that had been so brutally lost. That discovery process was led by Mr. Gao Wenshan, one of the first professors to graduate from the Tianjin Institute of Physical Education, Professional Wushu Program. In 1979 he first heard there was a Northern Shaolin. At the beginning of the 1980’s Mr. Gao took part in a Wushu performance in Tianjin and met up with Shang Bao Liang, the 6th Successor of the Northern Shaolin Gong Fu(see Chapter 3). After that he visited Jixian many times looking for the Temple, and finally found the 13 storied pagoda that led him to first suspect that it was the answer to his long quest for the North ShaolinMonastery. Following that he wrote the book: Research of North Shaolin Temple (北少林寺考) which proved to be a major contribution to further researchers.

“Following a clue given by Mr. Gao, a journalist came to the Wa Yao Village. Standing in the yard of Wei Fang, a villager, he saw the Pagoda, a “white Buddhist pagoda towering like a giant.” Wei Fang said that people called it the “Rouge Tower” and it is in fact the site of a gem Buddhist Pagoda. He subsequently found out that Chinese soldiers had held meetings there during the War of Resistance against Japanese Invaders. “The Japanese invaders fired all the temples here, and only this Pagoda survived.”

Reconstruction after the wars

It’s been more than 70 years since the destruction of the North Shaolin Temple but for the past five years the North Shaolin Temple has been undergoing reconstruction with funding from the Songshan Shaolin Monastery and Tianjin government; not a copy of the old North Shaolin Temple, but a larger, and even more beautiful temple, with architecture based on Song Dynasty designs and built in the traditional Chinese manner using Dougong – a system of interlocking wood brackets on top of columns supporting crossbeams with the brackets formed by bow shaped arcs, called Gong, and cushioned with blocks of wood called Dou. The temples contain no nails.

The (re)construction of Northern Shaolin Temple is being done in several stages. The first stage started on June 5th, 2009 with a total proposed area of approximately 8,000 meters.

Two of five main building have been built – two great classical Song Dynasty designed Buddhist Temple halls – the upper one – Sutra Hall (Cang Jing Ge also called Fa Tang Hall – a library for sacred scriptures) is painted with divine glory in immaculate detail and beauty, the other just below – Prayer Hall (Tian Wang Dian) – unfinished as yet and appearing rough-hewn but magnificent in its enormous simplicity and elegance. In a recent interview (July 28, 2013) the newly assigned Head Monk of the Northern Shaolin Monastery Shi Yan Pei said the next major building to be built would be the monks living quarters where over 100 monks will live. When complete the reincarnated temple will include the following:

入口园区 Entrance garden, 2.大殿区 Central Temple/Hall/Library area: Zhong Zhou Hall (Center Hall), Cang Jing Ge (Fa Tang) Sutra Hall, Shan Men (Entrance Gate Hall), Tian Wang Palace (Heavenly King Temple), 观音殿区 Guan Yin Palace (Bodhisattva Temple), 3.生活区 Monk living quarters, 4.演武区 Wushu practice area, 5. 遗址区 Tower and forests site – Ta Lin – ancient Tower-forest – Tombs up and behind the Temple, and a 6.Performance area. According to media reports, Songshan Abbot Shi Yongxin stated: “Attention to minute detail is being made to integrate the design of the buildings with the natural environment, and to ensure that the natural landscape is preserved during installation of their advanced information network, solar energy systems, air conditioning, and heating.”

The village around the North Shaolin Temple (Jixian Guan Zhuang Zhen – Wa Yao Village) is truly rustic and most people, especially the young are very much looking forward to the economic prosperity that will come from the (re)opening of the North Shaolin Monastery though owners of guesthouses and farms very close to the new construction site are concerned they will be forced to move as happened during the construction of the Songshan Shaolin 30 years ago.

In August of 1999, Abbot Shi Yong Xin inherited the Shaolin in a state of extreme disrepair both in terms of its physical structure and Vinaya (traditional monastic rules). Most will agree that he has done a magnificent job rebuilding the Songshan Monastery to the point of rivaling its ancient glory and realigning it with its roots in Vinaya designed to strengthen the spiritual foundation of the monastery. Though the Songshan Shaolin Temple has come under some criticism for being “too commercial,” and overly focused on the martial arts, the North Shaolin is being planned from the beginning to be more focused on traditional Chán Buddhism. In all fairness to the Songshan Shaolin, the commercial enterprises are outside the temple area and tourists are only allowed within some parts of the monastery. As with most monasteries, some monks prefer to live secluded from the public whereas others research and teach, and others are involved in social-work kinds of things. Songshan Shaolin also runs a large orphanage. That shops outside the Temple grounds sell things like plastic “Shaolin” swords is no great surprise, such things are done at landmark locations all around Europe and the U.S. as well. Songshan Shaolin Temple was recognized as a World Cultural Heritage site in 2010, one of only 39 in China.

Based on interviews with numerous Shaolin monks living adjacent to the North Shaolin construction area it appears this temple will differ considerably from Songshan in other ways as well, for example most of the monks seemed uncertain if the huge Ta Gou Martial Arts School from Songshan will be incorporated in the North Shaolin Temple area, or even nearby. It is the only martial arts school open to the public inside the Songshan Shaolin Temple. Based on its’ location and history it seems likely that the North Shaolin Temple was always a very special place even within the Shaolin Temple family. The differences are many:

North Shaolin Monastery is not located so close to any city as Songshan Shaolin is to Dengfeng and Luoyang. In 493 Luoyang became the capital city of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386 to 534) and the Eastern Capital during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). North Shaolin’s remoteness enhances its’ ability to remain pure of city influence and allows the monks a more pristinely natural environment – rather like the Buddhist sages of old – in which to pursue enlightenment. The North Shaolin Monastery specifically and Jixian (County) in general was geographically closer to the action when it came to foreign invasions and thus subjected to the greatest martial forces from the north and overseas. Panshan people certainly pride themselves on being “straighter” than peoples to the south.

Conclusions

If the peace loving and enlightening philosophies of Buddhism married to the absolute discipline required for mastery of martial arts forms a kind of ideological crown for China, the North Shaolin Monastery may be the jewel in that crown. Songshan Shaolin is the parent, older, bigger and far better remembered by history, but by virtue of its remoteness, the ruggedness of the Panshan mountain folk focused by the resistance, and having learned the lessons of Songshan Shaolin in 1928 (e.g. fighting the warlords using the monastery as a base isn’t a good idea), the North Shaolin survived to fight a little longer during the darkest days of Chinese history. The completeness of North Shaolin Monastery’s obliteration is a testimony to its commitment to the cause of freedom from foreign domination. In some ways its darkest days were its brightest in that the light of liberty must from time to time be replenished by the blood of patriots. How many if any monks were there at the end, and if any or how many survived is unknown at this time and further research is clearly needed to make this research more complete.But even after its destruction the Monastery lived on helping provide pieces of its broken body to the homeless nearby who were still living – often in caves – under the terrible shadow of brutal oppression. People who have never been in a war, or been refugees from a war can look down on those homeless souls struggling to survive the later years of the war, and accuse them of “looting” the Shaolin Monastery (and Emperor Kangxi’s palace) however they were doing what had to be done to survive as best they can. Looking around the mountain one can even today find old caves with sections that have been shored with bricks and stones from the old monastery and one can only marvel at the resilience of those that stayed and hung on to the land, preferring to risk their lives and honor to cling to the mountain that is their heritage. Thus the monastery lived on after its death and today is being reborn upon and incorporating pieces of its old self. The life of the Temple however was and is not in the bricks, stones and timber, but in the honor and truthfulness of its teachings. The old monastery never really died. It lives on as long as there are those who remember and honor the teachings of the old masters. Though so much was lost most of the teachings and culture have survived and lives on today.

Every Shaolin monk memorizes this poem/prayer before his/her ordination. When someone becomes a monk they enter upon the path of enlightenment and let go of earthly desires and attachments including to their biological family. But as a monk they are never alone. Memorizing this poem is a prerequisite to joining the ShaolinChán (Zen) Buddhist family. Generation names in Chinese culture may be the first or second character in a given name. Shaolin monks are usually called: “Shi” followed by two given names. This poem provides the first of the two given names. So, if a monk’s master was Shi “Yong” Xin for example, his disciples would be called: Shi “Yán” something, as Yán comes immediately after Yong in the poem. After the seventy generations the poem repeats. This generation/lineage middle name poem cycle is common in large and/or distinguished families in China. The following 70 character poem was written by Xueting Fuyu (雪庭福裕 1203–1275):

Read from left to right all the way across – Interpretations can be found below

嵩山少林寺曹洞

正宗传续七十字辈诀

福慧智子觉了本圆可悟

周洪普广宗道庆同玄宗

清静真如海湛寂淳贞素

德行永延恒妙体常坚固

心朗照幽深性明鉴崇祚

忠正善禧祥谨志原济度

雪庭为道师引汝歸铉路

Songshan Shaolin Temple Generations

Songshan Shaolinsi cáo dong

嵩山少林寺曹洞

Authentic seventy generation mnemonic

zhengzong qishízi bei jué

传续七十字辈诀

- 福慧智子觉 fú hui zhi zi jué

Literal: Blessed intelligent wisdom virtuous awaken

Interpreted as: Only the holy person can understand the way and then attain wisdom and bliss. - 了本圆可悟 liao běn yuán kě wu

Literal: Understand clearly, original source, fullness, can realize

Interpreted as: Using the whole to see the principles you may understand the way. - 周洪普广宗 zhou hóng pu guang zong

Literal: Widespread, great, universal, broad, clan/school/ancestor

Interpreted as: We must spread Chán (Zen) like the rays of the sun all over the world. - 道庆同玄宗 dao qing tóng xuán zong

Literal: natural/ethical path, celebrate, together, deep/black/mysterious, clan/school/purpose

Interpreted as: All the branches of Buddhism celebrate the same root. - 清静真如海 qingjing zhenrú hai

Literal Translation: Peaceful and quiet, Tathata (true character of reality; suchness) ocean

Interpreted as: Clarity and stillness are deep as the ocean. - 湛寂淳贞素 zhan ji chún zhen su

Literal Translation: Deep/crystal clear, silent, pure/honest/genuine, loyal/chaste, nature/essence/element/always

Interpreted as: When you abandon attachments your true face emerges. - 德行永延恒 déxíng yong yán héng

Literal translation: Virtue, always/everlasting, extending, permanently

Interpreted as: Only virtue is never ending. - 妙体常坚固 miao ti cháng jiangu

Literal Translation: Fantastic system/style, always firm/solid

Interpreted as: Your pure heart never changes - 心朗照幽深 xin lang zhao youshen

Literal Translation: heart/mind/center, bright/clear, illuminates brightly/clearly, serene/hidden depths.

Interpreted as: When your heart is still, its’ brightness will dispel the darkness. - 性明鉴崇祚 xing míng jian chóng zuo

Literal Translation: Moral Character, bright/clear/open/perceptive, reflection/warning, esteemed, blessing/throne

Interpreted as: Your true nature is the highest. - 忠正善禧祥 zhong zheng shan xi xiáng

Literal Translation: Loyal/devoted/honest, just/upright/straight/honest, virtuous/benevolent/kind, joy, auspicious

Interpreted as: If you are loyal, upright and kind, you will receive happiness and peace. - 谨志原济度 jin zhi yuán ji du

Literal Translation: Careful/solemn, aspiration/the will, original, to aid/help/assist, tolerance/accomplish

Interpreted as: Always remember your Buddha heart. - 雪庭为道师 xuě tíng wéi dao shi

雪庭福裕 Xueting Fuyu was the Shaolin Abbot that wrote this poem

Literal Translation: Snow/bright, main hall/front courtyard, purpose/reason, natural path/the way/morals, teacher/master

Interpreted as: Follow The Way (Dao) of Master Xueting (Fuyu) to enlightenment. - 引汝 歸铉路 yin ru gui xuan lu

Literal Translation: To lead/guide/cause, thou/you/your, return, base/platform/foundation, road/journey

The Songshan Shaolin Monastery was destroyed many times during its history and North Shaolin once too. But the Spirit of Shaolin lives not in the buildings or statues, the scriptures or sutras but in the hearts and minds of those that elevate it beyond the ordinary illusions of the material world. It is a moral ideal, a place that can be anyplace, anytime, (here and now are real, everything else is illusion) where people can clear their minds and work towards enlightenment(mainly through meditation) and in the case of Shaolin aided by the discipline of the world’s premier martial arts. But, this is only an illusory staff pointing to the moon melting under the glare of an old master. Ultimately one can at best defeat one’s self and truly awaken. Each strike, kick, and punch is an expression of the ancient way, and each welt received is an admonishment from the masters – a new awakening of the most immediate kind, a nudge to climb out of the confining self-made box of mind and see clearly. The human mind is too small to comprehend this, so let it go. As many old masters said: “The mind dies on the meditation cushion.”